On personal identity and growth

Don't let an idea of your past self keep you from becoming what you want

Accounts of personal identity

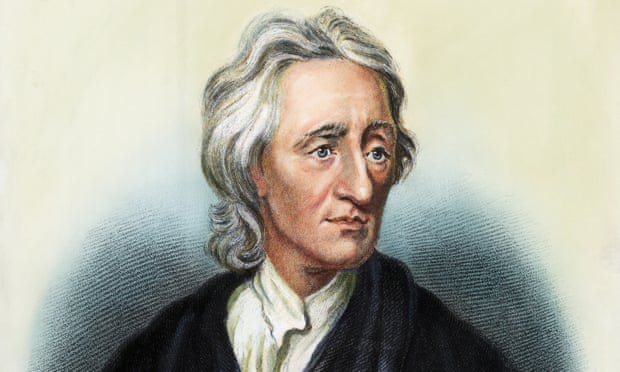

John Locke

We often approach the idea of self-identity as a distinguishable and unchanging body of consciousness. Its a concept that is both intuitive and practical, it provides us many desirable notions: a sense of ownership over our thoughts and bodies, accountability, and, among many other important things, persistence.

The sense of persistence to personal identity is key, it is what allows us to connect our present selves to a distant past when we were just kids. A lot, if not almost everything, has changed since. But by recollecting being children, we connect memory with identity. More importantly even, it is the very sense of persistence that allows us to associate a succession of events from our upbringing to being shaped to what we are today.

Persistence helps us derive uniqueness too, there can only be one of each as no one has really been through the same succession of events. We are also very much alone in the amount of memories of ourselves we hold. No one else could’ve known how you have felt. This deep level of psychological continuity is our identity.

Or so thought English philosopher John Locke. And his idea probably encompasses the beliefs of many people before and beyond his lifetime. To him, we are what we can remember of ourselves. And although this may not be the most complete account of what personal identity is, it is an undeniably big aspect of how we describe ourselves to this very day.

David Hume

To challenge this view, Scottish philosopher David Hume, known for his fulminating scepticism, questioned the existence of a “self” altogether. Hume’s “Bundle Theory” is not that complicated. It is a mere consequence of his maxim that “all ideas come from impressions (experience)”.

If impressions are not persistent, then there can be no idea of “a persisting self”. When we think about our own “self”, we are just associating sensations of hot, cold, light, dark, pleasure, pain.. over time. Thus, “we” are just a bundle of impressions. And when it comes to memory, we can’t even piece them together whole again. If we give ourselves another five years to revisit a memory of our childhood, it will have changed.

Hume also cares enough for his argument to justify why we mistaken ourselves into believing in the “self”. He states, perhaps irrefutably, that we have a strong inclination to call different things “the same” just because we can’t distinguish between their differences as noticeably. Every day the sun rises, but not the same way. We grow old fairly slowly, and even if we enjoy routine, we are changing by the minute. Life demands that we rise up to changing circumstances by the day. Where do we draw the line for this “sameness” in light of constant change?

Hume’s account of personal identity is a liberating one. We are nothing but a sum (a bundle) of distinct, separable and successive impressions. There are no necessary connections between distinct existences either. We just fail to perceive change and approximate similarities for equalities.

Practical implications

Both ideas of identity are fairly persuasive. While Locke’s position may sound like an articulate version of present day common sense, Hume’s arguments can’t be easily refuted.

Taken in absolutes, the Lockean account of identity is problematic by Hume’s scepticism, as we can’t even connect between seconds worth of changes logically. If there is something of a “personal identity”, memory certainly plays an important role in defining it, but memories are ultimately a bundle of incomplete collections of impressions that we forcefully try to piece together.

On the flipside, we can’t simply give in to Hume completely, as this would imply us to give up the very possibility of a social order. How to make sense of all the commitments without “a persistence in the self”? Is “the you from today” accountable to the promises made by “the you from yesterday”? How to make sense of contracts, marriage, the raising of children, the incurrence of debt, without it?

It really seems like Locke was onto something on his articulate common sense memory argument. Without it, there is nothing keeping us from exploiting one another for personal benefit. Memory simply has to matter.

However, I do personally think Hume has the upper hand here. While there may be no necessary connection between events in our frail memories, we take it upon ourselves to act as if memories meant enough to constrain our future decisions. We may not be obliged to uphold our commitments by logic, but we certainly desire to live in a world where each other’s words mean something, and they can only have meaning through some practical idea of memory.

We are expected to remember our wedding vows, to learn how to protect and raise our children, to pay our dues, to abide by the law, to always be responsible and caring. But when we comply to those we make this choice every second of each day. It is ultimately just a recurrent choice.

There’s more to this. And this is where I try to make my humble contribution to these two Goliaths of the history of human thought. I suggest we take Hume’s sceptical account on a positive light, and use Locke’s idea of memory to motivate us into a growth trajectory towards who we want to become.

Once liberated from the idea of “a self that is shaped by our memories”, we are on a much stronger standing to think about personal growth. If we are not a closed case of who we have been, we can waste less of our energy revisiting certain limitations we may have experienced to focus on what’s ahead. If change is inevitable, embrace it, give it purpose and steer your future towards something that appeals to you.

Liberated, we don’t need to worry about having been the person who had issues with multiplication tables in primary school (you are not born without the talent for math because of it), or the late bloomer adolescent that suffered bullying for lacking physical prowess (it does not mean you won’t find yourself a physical activity you’ll love later in life).

We are not defined by the criticism we faced for not having met our boss’ work performance standards (accept that this is a part of growth, welcome some of it).

We don’t need to be the person that disappointed a loved one, even if only weeks ago (show responsibility and unchain yourself from the person you were by not repeating the same mistake).

Naturally, we are not even those cherished memories that won’t come back for some particular reason (we don’t need to seek the same feelings we had then. Let’s hope for new, better ones).

We are free to pursue what we want to be, right now. In fact: always.

In a nutshell, today’s post is about two takeaways.

First, learn to appreciate that people’s commitment to you are about a succession of millisecond decisions, their accountability to you today is fundamentally a choice (and, by the same token, yours to them). Be grateful for each choice. Second, don't let an idea of your past self keep you from becoming what you want.

This is all for today. Thank you for making it this far.